Our motto in the newsroom is "everybody has a story." The telling of those stories can be entertaining, enlightening, inspiring, even disturbing, but it also serves as a record of history.

It's not just the living who have stories to tell, however. If everybody has a story, then every grave marker has a story as well.

This fall, some of the graves at Battleford Cemetery were moved. At risk of sliding down a slope into the valley of the North Saskatchewan River, graves from the late 1800s and early 1900s have been relocated. Members of the North-West Historical Society are relieved, as the danger the graves have been in for some time now has weighed heavy on their minds.

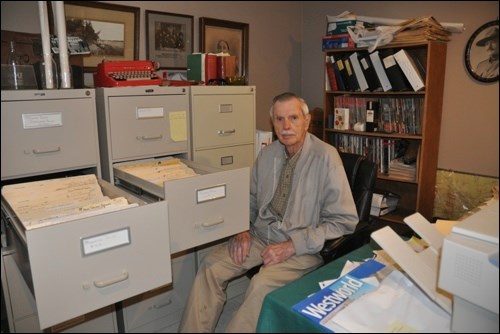

One member, Don Light, has been deeply involved in the plight of these graves and others throughout the region, including graves in the North West Mounted Police Cemetery in Battleford. A Battleford-born historian who has accumulated an exhaustive library on Canada's Mounted Police, Light has been instrumental in identifying, marking and, in some cases, restoring the graves of North West Mounted Police and Royal Canadian Mounted Police members throughout the region. The RCMP makes funds available for this purpose.

With each of the graves lies a story, some documented more thoroughly than others. But lack of information doesn't mean those lives were any less lived.

Among the graves moved in the Battleford cemetery was that of Supt. John Cotton, who was only 45 years old when he died May 7, 1899. In 1996, Battleford Telegraph columnist Jim MacNeill wrote about John Cotton, whose grave at that time was already at risk of tumbling into the valley.

Cotton's story is one of a promising young military man's move to the police force, rising to superintendent rank by the age of 29. He served at Fort MacLeod, Fort Walsh and Prince Albert before coming to Battleford to command the NWMP post there.

He was popular with the townspeople, admired for his marksmanship skills and was considered a fair commander by his men.

In 1889, he married the daughter of John A. MacDonald's minister of the interior.

A little over a year later, on a day when Cotton was away on duty, his wife died within hours of delivering twins. Within three months, both twins – a son and a daughter – had also died, a series of tragic losses for any man.

Although he married again – his late wife's sister – he didn't move on to ripe old age. In December of 1898, as reported by the Saskatchewan Herald, he was seized by an attack of quinsy (an abscess around a tonsil) and, by May of 1899, succumbed to pneumonia. He was buried in a blinding snowstorm.

Cotton's grave is no longer in danger of being lost. Thankfully, MacNeill's column and Don Light's research will ensure that his story is not lost.

Carrying on a family tradition of keeping history alive, Light has been active in seeing that members of Canada's Mounted Police are remembered with dignity. He has been made an honorary member of the Saskatoon Division RCMP Veterans’ Association in appreciation for his dedication to preserving Mounted Police history. One of the projects he has undertaken to preserve that history is chronicling thousands of references to the Mounted Police from the Saskatchewan Herald newspaper from its first edition in Battleford in 1878 to the last edition in 1938.

Born in 1932, Don Light is the grandson of Staff/Sgt. Frederick Walter Light of the NWMP, who was stationed at Fort Battleford where Don’s father, Frederick George Light, benefactor of the Fred Light Museum, was born.

Light and his brother, the late Doug Light, grew up to follow in their father's footsteps, preserving artifacts and documenting history pertaining to Canada's famous police force and the story of the prairie’s First Nation people. Their interest was sparked by the influence of their father, grandfather and uncles Cst. John Green and Supt. Ernest William Bavin. Bavin started his career in Battleford and ultimately headed up the first intelligence division of the RCMP at the outset of the Second World War, serving with Sir. William Stevenson, the subject of a famous book titled “The Man Called Intrepid.”

Light, along with the late Ross Innes, son of the man who "saved" Fort Battleford from obscurity after its closure, spent many years restoring existing gravesites and marking unmarked graves of Mounted Police members, both RCMP and NWMP, throughout the region. These graves are found in an area extending from Major in the south, Meadow Lake in the north, Duck Lake in the east and Onion Lake in the west. The project was realized with the support of Insp. Earl Peters, a former commander of the Battleford Detachment, who undertook to secure the needed funding at that time.

Most of the 100 graves found in need of restoration or marking are done. But Light still has some on his radar, and does a road trip throughout the region every second summer to check on them.

One of those is located at Wilkie, the grave of Cst. Arthur Raymond Vincent. Vincent's story was cut short in 1910 when he was 20 years old. While on a duck hunt near Snider Lake, about 15 kilometres northeast of Wilkie, he attempted to retrieve a duck he shot from the water. He was accompanied by Cst. Forbes. The following is taken from an account in the Wilkie Press:

"On account of the bush that surrounds the lake, Forbes couldn't see him and getting no answer to several calls, he concluded that something must be wrong, so immediately proceeded to the place where he had last seen Vincent, but on arriving at the spot he caught sight of his comrade's head disappearing in the water. Forbes called out to him that he would be with him right away and thereupon swam out to his assistance, but before he could reach Vincent the man shouted "goodbye" and sank, never coming to the surface again, and despite all effort of Forbes to recover Vincent he was unsuccessful."

In the Meota area in 1915, a RNWMP corporal, Thomas Wiltshire, suffered a mysterious fate, dying of poisoning by a caustic substance, but an inquiry couldn't determine the cause. He died in the Battleford hospital and was buried at North Battleford.

Wiltshire was in charge of the Meota detachment for four years and left a wife and two children when he was only 30 years old. Research done by Larry Romanow (RCMP retired) in order to properly mark Wiltshire's grave reveals his wife and children were supported on renewed rations and fuel until 1921, issued by Sir Robert Borden as a special case because Wiltshire did not qualify for a pension. Thereafter, the RCMP Benefit Trust Fund was established, which paid further annual assistance to Wiltshire's family.

Of course, not all Mounted Police died while in service. One of the graves found in the northwest is located at St. Walburg, that of Carl Werner Lind, who became a successful artist in his later life.

Born in 1891 in Sweden, he left home at the age of 15 to go to sea. He settled in the United States in 1907 and moved on to the Prince Albert area in 1910 to take up a homestead. In 1914 he joined the RNWMP and served at points in Alberta as well as Regina, Battleford and Turtleford in Saskatchewan. Toward the end of the First World War he served as a member of the RCMP on overseas service in France. When he returned, he worked with the Hudson's Bay Company as a purchasing agent. His travels through the north country inspired his paintings of wildlife and wilderness. During the Second World War, he re-engaged as a special constable, doing guard duty at Vancouver and Patterson, B.C.

Lind died at his home in St. Walburg in 1961.

There are still a number of Mounted Police graves in the northwest that Light would like to see better maintained and some he would like to see moved to the NWMP cemetery in Battleford, located south of the Fred Light Museum on Central Avenue.

One of the graves he would like to see relocated there is that of Cst. James Edward “Pete” Evans, presently located in an old cemetery near the Meadow Lake golf course. Evans, who served in Battleford, was one of the Canadian volunteers who sailed up the Nile River to Khartoum in Egypt in 1884 to save the imprisoned British General Charles Gordon. Although Gordon had been killed before they arrived, the expedition brought fame to Canadian voyageurs.

The RCMP dedicated the NWMP Cemetery in Battleford in 1973 during their centennial year. It was first used during the Northwest Rebellion. Barney Tremont, a rancher and ex-Dominion Telegraph employee, became the first victim of the unrest and was buried near the Roman Catholic Church. Other local victims of the rebellion were buried beside Tremont, including those killed at Cut Knife Hill. Following a typhoid epidemic a year later, when several police victims were interred there, the spot was designated as the NWMP burial ground, even though townspeople were buried there until Battleford's public burying ground was established in 1889.

The most recent police burial in the NWMP cemetery was in 1982, when Supt. Ernest William Bavin, aforementioned as Don Light's uncle, was buried there (and his wife in 1987). Born in Cheltenham, England, Bavin emmigrated to Canada in 1908 and joined the RNWMP. For the most part, he served in the Battleford area where he met and married the former Constance "Birdie" Light, Fred Light's sister. During the First World War, he served overseas, returning to Canada in 1918 where he joined the Alberta Provincial Police. When the RCMP and APP amalgamated in 1932, he was posted to Ottawa as chief preventive officer. He later became the RCMP's first intelligence officer.

He retired from the RCMP in 1941 with the rank of superintendent and joined the British Security Co-ordination Service in New York, serving under Sir William Stevenson until the end of the Second World War. He retired to Victoria, B.C. in 1945. At the time of his death, he was the oldest living ex RCMP officer in Canada.

Other burials from the 1900s were Cpl. Frederick Johnstone Bigg in 1967, Cpl. Benjamin McCubbin Kerr in 1964, Cst. William Hamilton Minshull in 1960 and Supt. Christopher H. West in 1935.

Every grave in the NWMP cemetery has a story, some documented, some not. In fact, some are not even marked, as a grass cutting incident in recent history resulted in markers being removed without their locations being recorded. Even the first man buried there, civilian Barney Tremont, can no longer be accurately located.

Another of the unmarked graves is that of Const. Alex E. Cowan whose death was reported in the July 12, 1886 edition of the Battleford Press. This young man was a brother of another Cst. Cowan who had been killed at Fort Pitt.

The Press reported that Cowan had been found missing from his tent one Wednesday morning, with a dummy occupying his place in the bed. The report reads:

"An examination of his kit showed that he had not taken anything with him except the partial suit of clothing that he wore, so that the idea of desertion was set aside. At an early hour in the morning a portion of his clothing was found on the riverbank, which led to the supposition that he had been drowned. The river was dragged on Wednesday and Thursday without success, but on the morning of Friday one of the barracks watermen discovered the body about a hundred and fifty yards from where his clothing had been found. The body was taken to the barracks and on Saturday was buried with military honors beside the other members of the force who lie on the banks of the Saskatchewan."

These are just a very few of the stories to be found amongst the Mounted Police resting in the Northwest.