This past Independence Day weekend in the United States reminded me of another momentous July 4 that happened 25 years ago here in Canada.

Back in 1995 on that date, I attended the Paul Bernardo murder trial in downtown Toronto, one of the biggest and most famous trials in Canadian history.

This trial was a media sensation in Canada back in 1995, and I was there to cover it — but not as an accredited media member. Instead, I was there that day reporting as a student from the journalism program at the University of Western Ontario.

There were four of us who went up to Toronto to cover the trial that particular day as a J-school class assignment. Even though I filed my report on it, I never did get around to publishing my account of what happened that fateful day in any actual media outlet — until now.

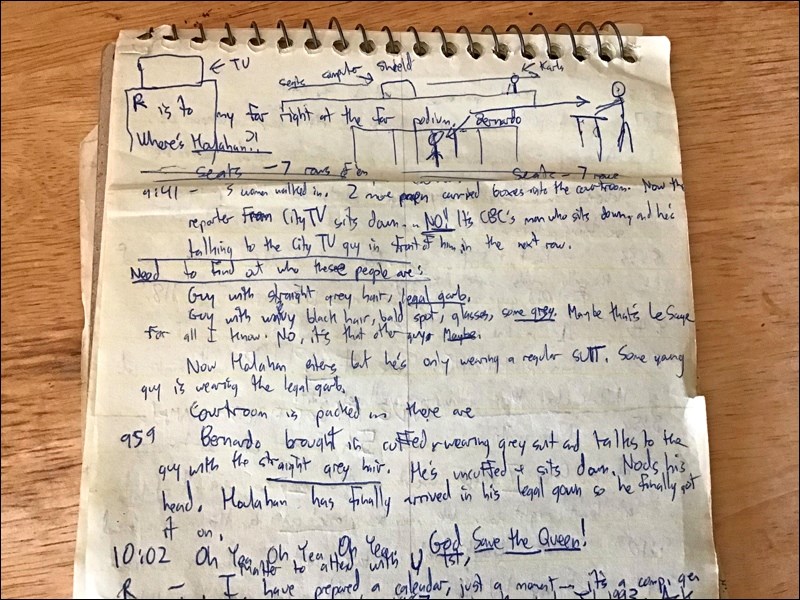

Recently, I looked through a box of my old materials and came across my reporter’s notebook from the day that I covered the Bernardo trial. Looking through that notepad, the events and experience of attending Canada’s “trial of the century” came back to life, all these many years later.

The backstory of what happened in the case can be summed up by the word “horrific.”

Bernardo had been dubbed the “Scarborough Rapist” and the “schoolgirl killer” — the former because of a series of rapes in Scarborough and elsewhere in the late 1980s and early 90s, and the latter because of the killings of three teenagers in the 90s. It was the killings of Kristen French (of St. Catharines) and Leslie Mahaffy (of Burlington) that Bernardo was on trial for in 1995. The other teenager was Tammy Homolka, who died under murky circumstances after being drugged — initially, there were claims it was accidental.

I will not go into too much detail here on all of what happened — there are several books out there that tell the entire story. But I will touch on a major controversy that erupted, and it had to do with the involvement of Bernardo’s wife Karla Homolka in all three killings.

Prosecutors cut a deal with Homolka where she agreed to a 12-year manslaughter conviction in connection to the rapes and killings of French and Mahaffy, and the sentence included two years for her involvement with what happened with her sister Tammy. In exchange, the Crown got her testimony in the Bernardo case.

There was a huge outcry over this arrangement, dubbed the “deal with the devil.” A lot of people feel the prosecution let Karla off the hook lightly, and that she should have been convicted for murder and met the same fate as her husband eventually did.

July 4, 1995, was not just any day in the Bernardo trial; it was perhaps the most sensational one of the whole trial.

It was the first day for Homolka’s cross-examination, after she spent the previous several days on the stand as a Crown witness. This promised big fireworks, far bigger than what those Americans were planning south of the border.

I tried to do background research of the players in the case prior to my day in Toronto. In my notes I wrote down a “guide to the trial.”

It mentions Bernardo, charged with “two counts of first-degree murder and seven other charges related to the sex slayings of Kristen French, 15, and Leslie Mahaffy, 14.” It mentions Homolka, and also mentions Associate Chief Justice Patrick LeSage, Crown attorney Ray Houlahan, and Bernardo’s lawyer John Rosen.

Rosen. I remember clearly the way he carried himself in the courtroom. Before the jury entered he would just pace and stride around the court, with his arms crossed, looking like a guy ready to do battle. When he did do the cross examination, he had a booming voice.

Rosen’s job was to demolish Homolka and make her look complicit in the killings, and destroy the credibility of all she said about Bernardo the previous week. In my notes, I had written that Rosen’s “strategy is to show Karla’s adept at fooling people,” and that he was “looking for contradictions.”

For the group of us heading to Toronto, the day had begun very early at something like 3 a.m. in the morning.

We travelled the highway from London to Toronto. Once we got there, we had to cross our fingers and hope we were admitted into the courthouse. We didn’t have the media passes that the accredited media had, so we had to stand in line like everyone else from the public. The line was sure to be long. There was a huge public appetite for this trial, with ordinary people showing up as spectators in the court gallery every day.

Here’s what I wrote in my notes:

“Made it to TO in one piece. Camped out in front of the Court House waiting to get in. Dave and Mary have taken off for food so we’re here holding a place in line. When we got here we found a huge lineup of people waiting to get in; some have slept here all night. Seagulls are chirping, birds are frolicking. Lineup is a real motley crew, that’s the best way to describe it.”

We noticed there was a police officer on the scene, looking around to make sure no one cut the line and that no one got mugged. I noticed the media booths that were set up not far away. Later, we noticed someone holding a “Hang Bernardo” T-shirt.

We spent several hours killing time waiting to be allowed inside. At 8:53 a.m., the line started moving, and I wrote down that there was concern among the four of us that we might not all make it inside the courtroom and that we’d get split up.

Good news! As of 8:58 a.m. we had all made it, just under the wire before they closed the seating to the rest of the people in line. We were on the fifth floor with our tickets, waiting to go through security and then take our seats.

Once we entered the courtroom, there was more waiting. I remember marvelling at the scene of all the reporters sitting in several seats in the courtroom – all these big names I had recognized from the newspapers and TV stations.

Finally, at 9:59 a.m., Bernardo was “brought in cuffed, wearing grey suit,” and he sat in the prisoners box. The proceedings began in earnest when the court clerk, or perhaps it was someone else, stood up and said the words “oh yea, oh yea, oh yea ... God save the queen!”

After some opening discussions between the lawyers and the judge, the cross examination of Homolka began. What follows is the account that I recorded in my notes as best as I could:

Defence lawyer Rosen led off by showing pictures to Karla of her sister Tammy.

“That’s your sister Tammy lying on a gurney dead, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“You saw her on the floor of the bedroom ... That’s a picture you can’t possibly forget, is that right?”

“That’s correct.”

“... I would think those pictures, those nightmares, would have bothered your conscience every living moment.”

“Yes it did.”

Then Rosen showed another photo.

“See that pretty girl on the left, who’s that?”

“Leslie Mahaffy.”

“You knew what happened to her on June 15, 1991, right?”

“Right.”

What happened, Rosen went on, was the dismembering of Mahaffy. Rosen then showed another photo, this time of Mahaffy’s torso.

“You participated in that, didn’t you?”

(Sob) “Yes.”

Next, another photo.

“Who’s that?” Rosen asked. Homolka confirmed it was Kristen French, alive, at 15 years old.

Then Rosen showed Homolka another photo. It was French, “dead at the scene when dumped in a ditch, correct?”

“Yes.”

Rosen again asked Karla if the photos bothered her conscience and kept her awake at night. Then shortly after, Rosen delved into what happened around the time that Karla left Bernardo.

He spoke of events during the latter part of 1992 when “your husband was punching you out the odd time.” Rosen then went into an incident on the night of Jan. 4, 1993, in which Karla was assaulted and threatened. Karla ended up lodging a police complaint against Bernardo.

Rosen: “When the constable took the complaint about the domestic assault did you tell them about [Tammy, Leslie and Kristen]?”

No, Karla responded: she was “too scared.”

Later, Rosen asked if she called any police officer to talk about those three. “No, I didn’t.”

“What you did was have a heckuva time,” Rosen retorted.

“No, I didn’t have a heckuva time,” said Homolka.

Rosen then brought up an interview Homolka had done under oath where she had stated “as soon as I left him in the hospital ... I felt I was 17 years old again ... I forgot Tammy, I forgot Leslie and Kristen, I went out and had a great time.”

“And that’s what you did,” Rosen said.

“I did not have a great time,” Karla responded on the stand. “I had nightmares, I tried to make myself forget.” Homolka said she was always “watching my back.”

Rosen turned to Karla’s efforts to get a lawyer. Initially, she went to Virginia Workman.

“Your lawyer was Virginia Workman, right? And you saw Virginia Workman on your dad’s birthday, Jan. 25, 1993, isn’t that right?”

“Right.” She explained she was a matrimonial lawyer.

“But you didn’t say anything” about Kristen, Leslie or Tammy, asked Rosen.

“I didn’t do that because I was terrified of Paul,” Homolka replied.

“I was obviously not thinking straight or else none of this would have happened.”

Later Rosen asked several questions about her encounter with another lawyer, George Walker, and about trying to obtain blanket immunity. Rosen tried to show that Homolka knew more about the concept of blanket immunity than she was letting on.

“You know what it is, you know it’s pretty good,” Rosen said.

“I went to him and told him to do the best he could for me.”

Rosen delved into the plea agreement Homolka eventually made with the Crown, and the negotiations that went on.

“As part of the deal you were never charged with murder — charged with manslaughter, no sexual assault, no dismemberment of Leslie’s body.”

“I wasn’t involved in the dismemberment of Leslie Mahaffy,” Karla then responded, but she admitted “helping throw her over.”

I had written down that Rosen strode by and glanced at the jurors, and shook the plea bargain agreement in front of them. Very theatrical stuff. He lampooned Homolka for her jail sentence.

“Long sentence isn’t it?” Rosen then asked when Homolka was eligible for day parole, and Homolka responded “a year and a half.”

“Excuse me?” said Rosen.

“A year and a half,” she replied. It turned out Homolka was eligible for day parole Jan. 6, 1997.

Those exchanges gave you an idea about the tension in that crowded Toronto courtroom that morning.

But the theatrics didn’t last. The afternoon session was far less riveting: a series of exhibits and cards were presented as evidence and Homolka was asked about those.

The long day was starting to get to all of us in our group. I remember dozing off in my seat at one point, only for a guard to come over to say to me “no sleeping in the courtroom!”

Finally around 3 p.m. one of my tired-looking colleagues passed me a note that read “let’s go.” I wrote back “OK.”

We filed out, and headed back in the car to London, Ont., to file our stories.

I cannot tell you what happened to the finished story that I eventually typed and handed in. I am guessing it is in a box somewhere, but I did find a first draft that I had written down in my notebook.

It’s cringeworthy. “Cross examination began on Karla Homolka before a packed courtroom yesterday in the Paul Bernardo trial,” I wrote in the first paragraph. I should have cut to the chase and said Rosen had spent the day grilling Homolka.

I hope this wasn’t the final version that I handed in to the instructors, because it’s unreadable. But my notes and notebook from the trial — they’re gold. Awesome stuff.

Looking back 25 years later, I can’t believe how time has passed. It is amazing to think that my very first big trial as a reporter – a lowly student reporter – was one of the biggest cases Canada has ever had, in Toronto no less. Just a couple of months or so before, I was still living in Saskatchewan.

What a way to get experience in covering trials. It turned out to be good preparation for the media circus that accompanied the Curt Dagenais murder trial in 2009 in Saskatoon, and the Gerald Stanley trial in Battleford in 2018, as well as the other court cases in between that I have covered.

What I should emphasize is that my Bernardo trial experience was of one momentous day. I did not attend day in and day out, week after week, like some reporters had to do. Moreover, I didn’t really follow the case obsessively, either before or after. I probably should have, but the subject matter repulsed me. It was too much, with teenagers being sexually assaulted, killed and dismembered. I’ve heard stories of reporters getting “PTSD” from covering this case, having to live through the gory details of what they heard for weeks on end during the trial.

Covering the Bernardo trial was quite an experience, but from my vantage point one day of it was enough.