Community leaders on the nearby First Nations of Little Pine First Nation and Poundmaker Cree Nation, including Chief Wayne Semaganis of Little Pine, Chief Duane Antoine of Poundmaker, Little Pine councilor-in-charge of justice Richard Checkosis, along with elders, are trying to prevent crime in their communities by establishing an Indigenous police service.

Self-administered policing is one of many initiatives by First Nations people in Canada in recent years to counteract the effects of colonialism, displacement and government policy.

Indigenous police services are currently used in a number of locations across Canada. The Eeyou Eenou Police Force has a number of detachments in Quebec. In Alberta, there are the Blood Tribe Police Service, North Peace Tribal Police Services, Lakeshore Regional Police, and the Tsuu T’ina Nation Police Service. The Aboriginal People’s Television Network produced a series detailing the Stl’atl’imx Tribal Police Service, which has detachments in Lillooet and Mount Currie in British Columbia.

Saskatchewan’s only Indigenous police service, File Hills Police Service, is located near Balcarres, between Regina and Yorkton. The agency’s primary area of jurisdiction encompasses Carry the Kettle First Nation, Peepeekisis First Nation, Okanese First Nation, Little Black Bear First Nation and Star Blanket First Nation, including Wa-Pii-Moos-Toosis.

Jacob Pete, chairman of Little Pine Elder’s Council, is helping work out the logistics of the Indigenous police service. As well as working with the RCMP in roles such as constable and chief of police, Pete has helped establish Indigenous policing on Gull Bay First Nation (near Thunder Bay), and Louie Bull First Nation (south of Edmonton), along with the Dakota Ojibway Police Service, whose jurisdiction includes a number of areas in Manitoba. Pete was also adviser on the National Task Force on Aboriginal Policing, and has authored studies pertaining to justice and Indigenous people.

A Google search reveals some of the crime associated with Little Pine and Poundmaker. There have been a number of drug charges over the past few years, including a situation earlier this year involving drugs and weapons in which four people were charged. Murders and people going missing have also occurred.

Little Pine was in the news in 2015 regarding efforts to introduce traditional practices as consequences of crime. News stories at the time centered around the proposed practice of banishing drug dealers from the First Nation, which would also involve removing them from band-owned houses, and turning off power and water.

Pete said Chief Little Pine School has embraced certain disciplinary measures different from traditional western juridical measures. A student was caught with marijuana at a winter camp, Pete said, but instead of seeking to press charges, local decision-makers performed a shaming and had the student research, write and present an article about how drugs can harm the community.

Two years after discussions and using traditional disciplinary practices, crime continues on Little Pine and Poundmaker.

According to reports obtained by the Regional Optimist, RCMP calls for service in 2016 at Little Pine numbered 686. Sergeant Heath Robinson, stationed in Cut Knife, writes “substance abuse appears to be the root cause of the majority of the repetitive and serious crime occurring in the detachment area.” The report states drug activity associated with organized crime continues to be an issue and is “a contributing factor to violence and other criminal activity in the community.”

In 2016, Little Pine community leaders sought community consultation regarding the extent of harmful activity on the First Nation and measures to reduce it. The meeting was in Cree and scribes translated the words into English and wrote them down.

The comments from the sessions included community members expressing dissatisfaction with the RCMP. Complaints include experiencing slow response times to calls for service, a lack of visibility on the part of the RCMP, a lack of consultation regarding who should police the community, and frequent rotation of different policing personnel in and out of the community. Other comments included unsatisfactory quality of services, impersonal and bureaucratic policing styles, and community leaders wanting more decision-making power regarding policing.

The documents note problems that could be solved by a police service operated and staffed by Indigenous people. Pete said active community participation is necessary for policing First Nations, and familiarization with customs, traditions and expectations would make the process of integrating new police officers easier than integrating those who are less familiar.

Pete was at a school celebration with an officer new to the community.

“[The officer] was sitting by the door and he didn’t quite know what to do,” Pete said. “I went up to him, ‘Come and sit down with me in front.’ He says ‘What do I say?’ ‘Do your PR thing.’”

A song started.

“I said they’re going to ask you to dance, so you better dance, buddy.”

The officer didn’t seem to know what to do at the dance. Pete said “watch that guy beside you, do the same thing.”

The officer did a couple rounds, “and the third round stopped and the kids were around him for a change, which I think he made a hell of an impression that he could participate.”

Pete said police work in the community involves more than punishment.

“You gotta see those kids ahead of time when they’re not causing a disturbance.”

Pete referred to Indigenous people in Saskatchewan’s justice system as being “a big industry.”

Dr. Jason Demers, a sessional lecturer at the University of Regina, published a report in 2014 entitled “Warehousing Prisoners in Saskatchewan: A Public Health Approach.” It states “the Aboriginal population in Saskatchewan’s prisons is consistently over 85 per cent.”

Another distinctive feature Pete thinks an Indigenous police service could bring to the communities is policing style, and ways of administering justice.

Little Pine’s 2016 community consultation report states “the strong adversarial features of the Canadian Criminal Justice System will always conflict with the communal nature of our people. The inherent restorative and reparative features of our indigenous justice system will continue to be more appealing to a majority of our indigenous people.”

Pete said he advocates a policing model in which “you don’t have to charge everybody.” Mutual understanding of culture, values and worldview between police and community members, Pete said, leads to trust and mutual respect, increasing the chances of preventing criminal records in the first place.

Nevertheless, according to an agreement with the RCMP, Poundmaker and Little Pine already should have Indigenous police officers.

In 2014, Little Pine and Poundmaker chiefs signed a Community Tripartite Agreement which outlined how policing was to be administered on the two First Nations. The agreement lasts from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2018, with possible automatic annual renewals for the next 10 years if another agreement has not been reached. The agreement states the RCMP will assign three RCMP members who will devote 100 per cent of their regular working hours to the policing needs of Poundmaker and Little Pine.

The agreement states “Council” (Little Pine and Poundmaker band councils) must “provide a policing facility, on the Little Pine and Poundmaker First Nations” that meets the operational needs of the RCMP.

8.2 of the agreement states the RCMP “will exercise its best efforts to assign RCMP members who are Aboriginal or familiar with the need and cultures of the Little Pine and Poundmaker First Nations.” 8.3 states “where vacancies occur, the RCMP will exercise best efforts, subject to and in compliance with RCMP human resources and labour relations policies and governing regulations, to fill or provide coverage for such vacancies as expeditiously as possible.”

There is a detachment in both Poundmaker and Little Pine. Currently, the First Nations are policed by one corporal and two constables, reporting to Sgt. Robinson in Cut Knife.

RCMP Superintendent Mike Gibbs said staffing shortages are regular among police departments, but staffing detachments with Indigenous RCMP members, and with cultural experience pertaining to communities in which they work, is more difficult.

Gibbs said the RCMP would like to see staffing that reflects community demographics, which he said is likely to better serve the needs of communities than staffing that doesn’t. Regarding the situation of Little Pine and Poundmaker, Gibbs said staffing with Indigenous RCMP members, although available for a period of time, wasn’t available for the entire length of the CTA.

Other factors prevent the RCMP from satisfying the needs of First Nations community members, Gibbs said. Self-identifying as an Indigenous RCMP member is voluntary, thus some people who are of Indigenous ancestry decide against declaring, while for the sake of earning certain benefits, others declare while maintaining only meager connections to First Nations communities or culture.

Rank also limits certain candidates: Indigenous RCMP members of a certain rank wouldn’t be able to work in communities deemed to require different ranks. Gibbs said the career circumstances of certain RCMP members might make them not want to work on First Nations. Gibbs cited as an example an RCMP member nearing the end of their career, and with children in university, wanting to live in the city.

Gibbs said the RCMP supports the efforts of Poundmaker and Little Pine establishing a police service.

“Self-governance is important for First Nations people and the communities out there,” Gibbs said. “If we could provide the First Nations people that were able to speak the language, that would be awesome, but it’s the reality of it. We just don’t have that type of person to go around.”

To avoid some of the staffing problems the RCMP faces, Pete hopes to train Poundmaker and Little Pine community members and retain them. Pete said retired RCMP members have expressed interest in being involved.

With experience in security, Pete said he’s begun a security patrol, made of what he called “Peacekeepers.” Plans include administering an eight-person staff and a 24-hour central dispatch service to make response times quicker. Looking after elders would also be a priority.

Regarding the efficacy of First Nations police services, Oliver Williams, who was with the Stl’atl’imx Tribal Police Service, said in an APTN segment he noticed the criminal activities had reduced in the areas subject to tribal police.

“I don’t want to be so naïve as to say [crime has] disappeared, but it certainly has fallen off,” Williams said.

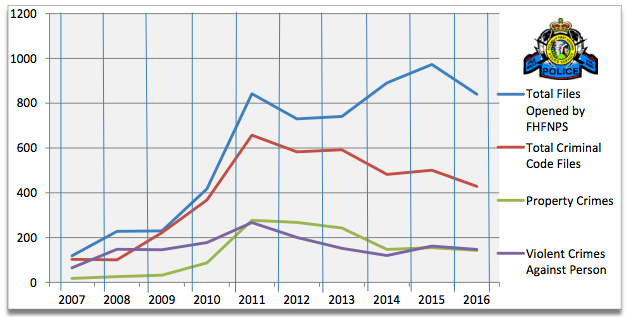

According to the 2016/17 annual report of the File Hills First Nations Police Service showing 10-year trends, total calls for service reached about 200 by the beginning of 2008, while the total calls for service peaked in 2011 with over 800. Total calls for service approached 1,000 in 2015.

Total criminal code files and violent crimes against persons were below 200 at the beginning of 2008, and peaked in 2011, when total criminal code files were above 600 and violent crimes against persons were above 200. 2016 numbers indicate total criminal code files decreased since 2011 to be above 400, and violent crimes against persons to be below 200.

“It should be noted that the numbers, while possibly reflecting an increase in crime trends, can be influenced by things such as man-power and public confidence in the police,” the report states.

Pete said the plan wouldn’t be to eliminate RCMP presence instantly, but rather integrate Indigenous policing gradually. A phased approach would “select and second an experienced senior RCMP member” to help implement the plan; keep the current CTA and replace those currently working as part of the CTA with qualified Indigenous police staff; and introduce “tiered policing,” which would involve direction from elders, and the delivery of police functions by peacekeepers, private security, community agencies, and volunteers.

The name of the planned police service on Little Pine and Poundmaker is Battle River Treaty No. 6 Regional Police Services. A press release issued on Oct. 26 states “police commission members from each band will be appointed to manage and operate the police commission. A chief of police will be responsible to the police commission for the administration and operation of the police services.”

About the Stl’atl’imx Tribal Police Service, Williams said the service was initially met with resistance from the provincial government in 1999, but resistance subsided once the service demonstrated its professionalism.

Governmental attitudes toward Indigenous policing appear to have changed now that Indigenous police services are becoming more common.

On Sept. 11, Chief Semaganis and Chief Antoine sent emails to provincial and federal government officials asking for $30,000 in funding to develop a proposal for an Indigenous police service. A letter from Saskatchewan’s Minister of Justice Don Morgan stated “the province of Saskatchewan is not in a position to fund this proposal” but encouraged efforts to work with policing authorities to establish an Indigenous police service.

The office of Minister of Public Safety Ralph Goodale, responding on Sept. 11, stated the message had been forwarded to the department and that the matter would be brought to Goodale’s attention as soon as possible.