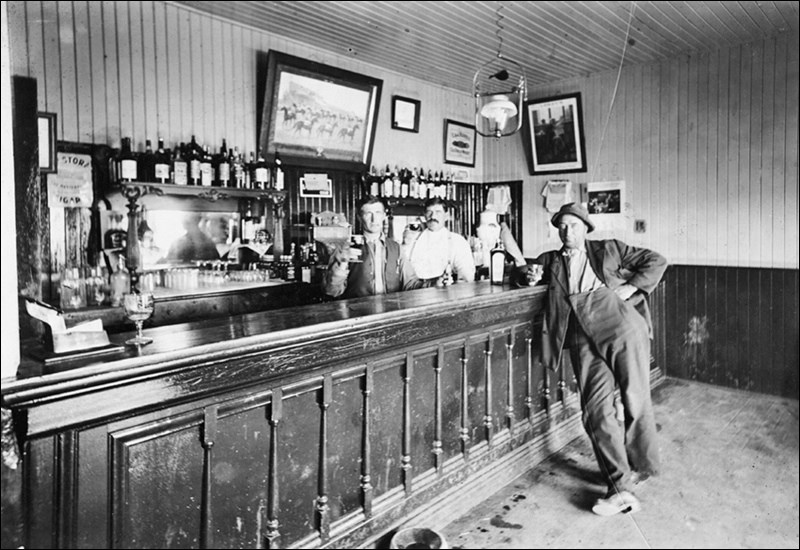

Saskatchewan’s hotel bars were busy places in the early 1900s. The typical hotel in 1910 had a long, ornate wooden bar complete with a large mirror behind it, brass foot rails and brass spittoons. A sign over the beverage room door read, “Licenced to sell spirituous or fermented liquors.” These were stand-up bars for men only – there were no chairs. Over the bar, the bartender served beer, wine, brandy and gin, as well as soft drinks. Whiskey sold for 10 cents a glass.

The hotel bars did a roaring trade. For example, the 30-room Carlton Hotel at Pense, built in 1904 at a cost of about $48,000, made $25,000 in a single year. “It had a large bar,” states the local history book, “which on one picnic day sold $1,000 worth of liquor, the liquor being purchased by the carload.” The hotel at MacNutt stayed open on sports days. “It was on days such as this that we usually sold 500 to 600 bottles of liquor in one day,” Philip Schappert, the hotel bartender recalled.

Things really got hopping on Saturdays. Farmers who hauled their grain for many miles stopped into the hotel to eat and quench their thirst after a hot and dusty journey. “With families dispersed into the country stores to shop, visit friends, and exchange gossip,” James Gray writes in Booze (1974), “the farmers had the opportunity [to slip away for a drink] if they had the urge.” T. L. Ferris described the scene in the Fielding history book. “A Saturday night was quite different from anything you might see today,” he recalled. “There were no street lights in those days and only the hanging light on the wide north porch lit up the entrance to the bar. We’d see noisy drunks come reeling out and many a fight livened up our evenings.”

Of course, some of these stories are the stuff of “rural myth.” For example, a tale is told about the North-West Hotel in Ceylon owned by William J. Coffron of a certain Irishman who had a few too many drinks and caused a disturbance. “Mr. Coffron got him upstairs and handcuffed him to the bedstead,” the Ceylon history book records. “Before long, he was coming down the stairs carrying the bedstead with him.” At the Strasbourg Hotel, rumour had it that a fellow rode his horse in and shot up the bar. Subsequent owners maintain that the bullets are still in the wall.

Concern about the high rate of alcohol consumption in Saskatchewan led to pressure from the Women’s Christian Temperance Unions (WCTU) and the Banish-the-Bar movement. Their battle against the evils of whisky resulted in an announcement by Premier Walter Scott in March 1915 that all bars in Saskatchewan would be closed as of July 1, 1915.

“We’ll have to close,” said Arthur Mason, proprietor of Saskatoon’s Royal Hotel. “There is no possibility of keeping open.” Mason’s prediction was not far wrong. The profits of the hotel bars were just about enough to make up for the deficit from the rest of the business. The glory days of Saskatchewan hotels – the days before Prohibition – were officially over.