Peat moss improves soil aeration, increases its ability to hold nutrients and water, and adds organic matter to the soil. It's an ideal amendment for adding to areas intended for lawns, flowerbeds, and vegetable gardens. And it is usually the largest component of most potting mixes (followed by vermiculite, perlite, sand plus minor amendments) used in pots, baskets and containers; finely milled peat moss (plus other components) is often used as seeding media.

Existing lawns can be "top-dressed" with a mixture of coarse sand and peat moss, especially following aeration. Very coarse peat moss can be used to mulch flowerbeds, but it breaks down rapidly and needs to be renewed annually. Other uses include wound dressing (even as late as the First World War) due its absorptive and antibacterial/antifungal nature and as a component in fish tank filtration systems to soften water.

Consisting of the leaves and stems of the sphagnum, peat moss is capable of holding over 10 times its weight in water. It's low in nutrient value, containing only about three per cent nitrogen, but excellent as organic matter. Its pH is between 3.0 and 4.5, making it useful for acid-loving plants such as azaleas and blueberries. Lowering the pH of our typically high pH (i.e. basic) prairie soils can also make nutrients more available for plant growth.

Considering all of its good characteristics, it's disturbing to read articles in gardening magazines and the popular press about the imminent demise of Canadian peat bogs. And, of course, it's always the gardeners who are to blame. There is almost always an attempt to guilt us into using alternate, sometimes inferior, amendments in an effort to be "green."

An initial impulse is to scream that it takes a lot more energy to process and bring a tropical coconut hull product to Canada than it does to harvest our northern bogs. But the crux of the matter is differentiating between the Canadian peat moss deposits and those of Europe.

Peat has been harvested and processed for thousands of years in Europe, mainly as a fuel. In Ireland, peat continues to be used as a fuel, primarily to run electric power plants. Yes, there is no doubt that European peat bogs are being depleted.

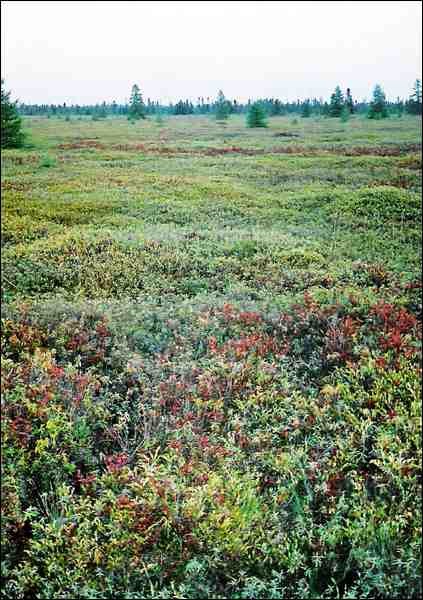

But there are more than 113 million hectares (270 million acres) of peat bogs in Canada. Less than 0.02 per cent of this area (6,000 acres) is currently being used to harvest horticultural peat moss.

What's more, peat bogs are sustainable and after harvest Canadian bogs are being restored to the wetlands they once were. Members of the Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association have developed strict guidelines with researchers, conservation and environmental organizations, and Environment Canada. Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba have provincial wetland conservation and management policies in place. Other Canadian provinces are in the process of developing these. Among the CSPMA guidelines are:

one metre of peat moss must remain once harvest is complete;

Bogs cannot be prepared for harvest too far in advance;

Reclamation should begin as soon after harvest as is practical;

A buffer zone of original vegetation must remain when bogs are cleared for harvesting;

Drainage systems must be compatible with the restoration of the water table after harvest.

Peat forms at the rate of one to two millimetres per year. It is accumulating nearly 60 times faster than it is being harvested. A study by the North American Wetlands Conservation Council (Canada) indicated harvested peatlands can be restored within five to 20 years after harvest. With responsible management policies, they are indeed sustainable, for Pete's sake.

- Williams, inducted into the Agricultural Hall of Fame in 2014, is the author of the newly revised Creating the Prairie Xeriscape and, with Hugh Skinner, Gardening Naturally, a Chemical-free Handbook for the Prairies. Her latest book, The Saskatoon Forestry Farm Park and Zoo: A photographic History, will be released shortly. This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (www.saskperennial.ca; hortscene@yahoo.com). Check out our Bulletin Board or Calendar for upcoming horticulture events in April and May.