NOTE: The term “Indian” is used in this article, as that was the word most commonly used to refer to Indigenous peoples during the period under discussion.

Indigenous people were not allowed to drink in Saskatchewan bars until 1960 – the same year they were granted the right to vote. The push for Indians’ right to purchase and consume alcohol began right after the Second World War.

Several thousand Indigenous men and women fought in the Canadian armed services during both world wars. When they returned from overseas, however, the out-dated Indian Act prohibited them from voting, holding powwows, and drinking alcoholic beverages. They were not even allowed to drink with their former comrades-in-arms at the Legion halls across Canada.

In 1951, the federal government made several changes to the Indian Act, including an amendment that permitted Indians to consume intoxicating beverages in licensed premises, providing that their provincial government allowed it. The Saskatchewan government, however, was not prepared to act. Premier Tommy Douglas, a non-drinker himself, was not in favour of drinking whether by whites or Indians. He also knew there was a divergence of opinion about drinking among Saskatchewan’s Indian leaders.

Nothing was done until July 27, 1960, when, with the issue of a federal proclamation, Saskatchewan Indians were given the right to purchase and consume alcohol. In the latter instance, they were not allowed to drink liquor on a reserve unless that reserve had been declared “wet” as the result of a referendum.

Hotel owners in Saskatchewan were solidly opposed to opening their bars to Indians. In May of 1961, Premier Douglas addressed the 30th annual convention of the provincial hotel association, urging them to be patient. “We are having this trouble,’ Douglas said, “because we are reaping the harvest of 50 years or more of making the Indian a second-class citizen. We are going to have to make up our minds whether we are going to keep the Indian bottled up in a sort of Canadian apartheid or whether we are going to let him become a good citizen.” He cautioned, however, that while the Indian had been given equal rights, he had no more right to break the law than the white man. “If he is drunk or causing a disturbance then he should be put out of the premises the same as a white man should. But he should not be put out just because he is an Indian.” (Regina Leader-Post, May 18, 1961)

Nevertheless, incidents of discrimination against Indians in Saskatchewan hotels began to occur. In January of 1971, for example, the pub in the Windsor Hotel in Leask was one of four hotels accused by the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians of refusing service to Indians. The beer parlor was divided into two areas, one with rugs and the other without, and Indians patrons were not served if they sat in the carpeted section. An Indigenous woman said she tried to sit in the “white area” three times and was told to move. In his letter demanding an investigation, FSI Chief David Ahenakew stated that while drinking might not be the most enlightened social endeavor, it was essential, “especially in such a milieu where defences are often lower and the cutting edge of racial tension more keenly felt,” that scrupulous attention should be paid to the basic civil rights of all Canadian citizens. (Regina Leader-Post, Jan. 6, 1971)

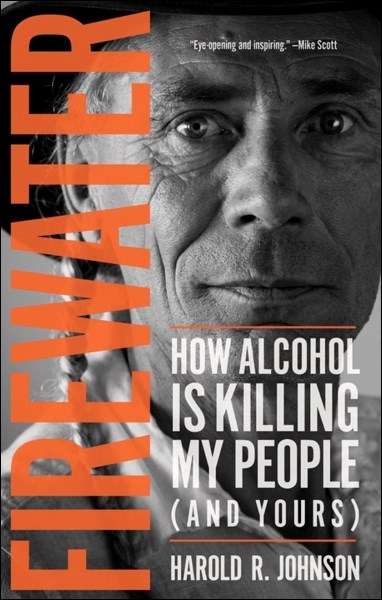

In his 2016 book, Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours),Cree lawyer Harold R. Johnson points out that during the negotiations for Treaty 6, the Indigenous people asked the Treaty Commissioner for protection from alcohol. This was written in the Treaty agreement. Thus, Johnson asserts, the change to the Indian Act in 1960 allowing Indigenous people into bars was, in effect, a Treaty violation. By the end of the 1970s, alcohol abuse was one of the biggest problems facing the First Nations of Saskatchewan.