I’ve heard a few people mention the impending turn of the decade, that perhaps this will be another “Roaring Twenties.”

But for some of the youngest among us, it may feel like a countdown, as in, they have 10 years left to the end of the world. The deadline, as in “dead,” literally, is 2030.

Two months ago, both of my kids told me they had heard other kids talking about how climate change was soon going to mean the end of the world, that they expected to die soon as a result. And at least one of these references was at church.

Then a few weeks ago I was at an Energy Safety Canada safety seminar in Weyburn, and one of the participants noted how their grandkids had heard or said similar things. Several other people piped up, echoing the concern.

As I type this, the lead story on the National Post app carried this headline: “‘We’re going to die’: Toronto mother says young daughter terrified by school presentation on climate change.”

Apparently, that Toronto kid isn’t the only one. This is becoming a widespread phenomenum.

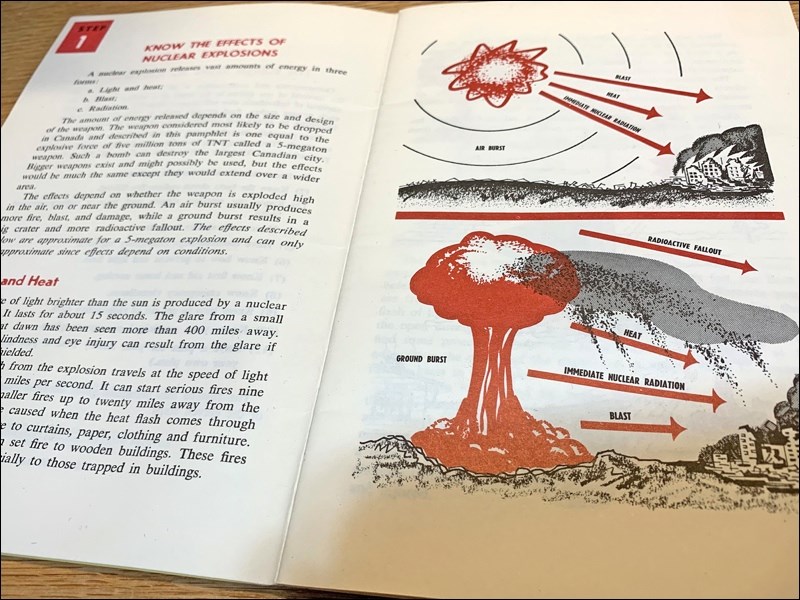

These climate doomsday forecasters need to take a lesson from the Cold War. If you want to scare the bejesus out of little kids in school, you don’t talk about melting ice caps and rising oceans. You teach them how to duck and cover under their desks when they see a brilliant flash, expecting that those desks and the bubblegum under them will protect them from the Bomb.

Hell, dust off an old film projector and show them some nuclear tests from the Nevada Test Site and Bikini Atoll (or I guess you could use YouTube.) Show them how to really make an island disappear, not with a rising ocean, but with 15 megatons of righteous fury! (The Castle Bravo test is one of my favourites. They figured it would be four to eight megatons, but someone goofed and it ended up being 15. Look it up, you’ll enjoy it! I did.) The Ivy Mike test also made an island at Enewetak Atoll vanish.

But if you really, really want to convince them your life will soon end, show them the film of the Tsar Bomba. That’s the Soviet nuke that came in at 50 megatons, whose shockwave was detected on its third trip around the world. And then tell them the Soviet scientists actually limited its output by half, since they were afraid of the enormous amount of fallout that would result from the 100 megaton, full-fledged weapon.

Then you can tell them about the string of radar stations, like the one about 12 miles west of Yorkton, that were built to detect those Soviet bombers on their way to destroy us all. And when they’re quaking in their shoes, kindly inform them that the bombers wouldn’t matter anyhow, because it would only talk about a half hour for Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles to get here.

That, my friends, is how you properly scare young kids into thinking the world is going to end.

The reality is that not much of the above has gone away. Yes, the number of nukes out there has been greatly reduced, and most are much, much smaller than the city-flattening five-, 10- and 25-megaton whoppers that were common in the 1960s. But there’s still plenty of megatons around to make us all glow in the dark. And the nearest active missile silo is precisely 50.0 kilometres from my front door. I checked on Google Maps.

As a child of the Cold War, I never did go through a duck and cover drill. I guess by that point, most of society realized the futility of it, so they never taught it where I grew up (I got a tour of the Yorkton radar base in Grade 3 instead). I learned all this on my own, while most everyone else was, thankfully for them, none-the-wiser. In cleaning out the old air cadet hall in North Battleford around 2006, I found a 1960s era nuclear survival guide issued by the government of Canada. Obviously some kids, a generation before me, were taught these things here.

Now we have Greta Thunberg. As she told the United Nations, “This is all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you!

“You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I’m one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!”

No wonder kids are scared.

Yet somehow, mankind has survived the impending nuclear holocaust. And if, indeed, we are changing the climate, we will survive that, too.

Oceans have risen and fallen for hundreds of millions of years. Nearly all the 3,400 metres of sediment under my feet in Estevan come from being at the bottom of an ocean. At the most recent glacial maximum, you could walk (on ice, mind you) where the Hibernia oil platform is currently sitting in 90 metres of water. First Nations learned how to adapt to the Canadian prairies once the ice retreated from Saskatchewan. Scratch that. First Nations learned how to adapt to nearly all of Canada, as it was covered with ice 20,000 years ago. They didn’t have the benefit of modern technology or heavy equipment, like we have today. If the oceans rise (some more, as they have since 20,000 years ago), we will figure out how to move a little further uphill.

No matter what Greta tells our kids, the world will not end.

Brian Zinchuk is editor of Pipeline News. He can be reached at brian.zinchuk@sasktel.net.