There was a great deal of anxiety on the part of Saskatchewan’s hotel owners when Prohibition came into effect in the province on July 1, 1915. With closure of the bars, their chief source of revenue was taken away.

Dramas large and small ensued. A month before Prohibition came into force, the Saskatchewan Licensed Victuallers’ Association issued a proclamation that all hotels would close as of July 1. “It isn’t a case of closing just to be spiteful,” stated Arthur Mason, vice-president of the association, “but simply because we can’t afford to keep open.” On June 4, 1915, the Regina Morning Leader challenged the hotel association’s proclamation, calling it both “a confession and a threat.” “The pretense of these men in the past has been that they existed primarily for the purpose of supplying hotel accommodation to the travelling public and that the sale of liquor was an adjunct to that business,” the newspaper’s editorial claimed. “The hotel men now confess that the hotel was merely a plausible excuse for the bar.”

Smaller dramas played out in Saskatchewan’s towns and villages. Prior to the enactment of Prohibition, there were 427 hotels in the province. By April 1917, the government reported that there were 237 places licensed as public hotels. Forty-six hotels had closed in the first three weeks following the banishment of the bars. Others threatened to close.

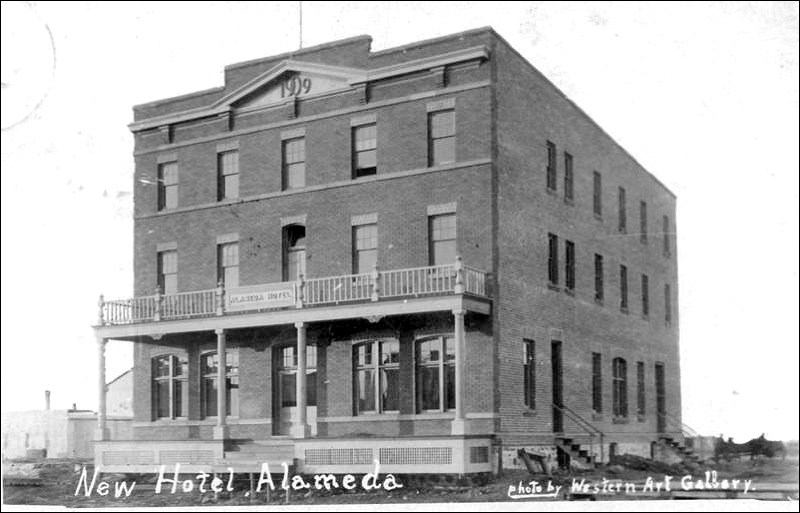

In Alameda, for example, hotel owner H. MacHouse closed the town’s only hotel immediately after Prohibition came into effect. It appears that he was attempting to pressure the community in order to gain both patronage and government subsidies. His efforts were successful, at least in the short term. In a letter to the editor of the Alameda Dispatch on July 9, 1915, MacHouse stated that he would experience heavy losses as a result of the new law, and that the success of the hotel would require the support of the people of Alameda and district. “I wish to say to the public that without their support and co-operation I find it is impossible to keep this hotel open.” MacHouse wrote. On Aug. 6, 1915, the newspaper reported that town council agreed to all the terms and conditions submitted by MacHouse, including that only one hotel license be granted in Alameda, and that the council turn over him the maximum grants and other concessions provided for hotels by the provincial government. MacHouse re-opened the Alameda Hotel on Aug. 13, 1915.

A major feature of the Hotel Act, passed on June 24, 1915 in conjunction with prohibition legislation, was a provincial grant program to towns with populations under 1,000 for the establishment of rest rooms and reading rooms in hotels “for the convenience and comfort of the general public.” The idea was to give a concession to the hotel owners who had lost their liquor licenses, and to transform the hotels into social centres. The government reported that by the end of 1916, provincial grants totalling $100,416.47 had been given for rest and reading rooms in 225 small-town Saskatchewan hotels.

The transition from bar to social space after Prohibition proved to be an uphill battle for small-town Saskatchewan’s hotels, however. In Landis, for example, the hotel struggled. On Jan. 31, 1918, the Landis Record reported that the hotel was not being patronized to the extent required to pay the bills. “To heat a house of the dimensions of the Landis Hotel, to pay hired help in order to give good service, and to furnish good accommodation, requires considerable outlay,” the newspaper stated. “If the proposition is not a paying one, the community is bound to suffer.” The editorial concluded that, “the hotel being a necessity, it should be patronized by the farming community whenever possible.” On Feb. 4, 1918, the Landis Village Council passed a motion levying one and a half mills on the village assessment for hotel support.

Government subsidies allowed the hotels to limp along, but they were no longer the paying propositions they had been before the bars were abolished.