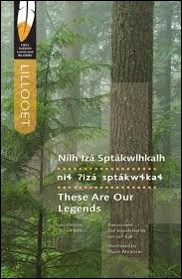

Narrated by Lillooet Elders, transcribed and translated by Jan van Eijk,

Illustrated by Marie Abraham

Published by University of Regina Press

$24.95 ISBN 9-780889-773967

University of Regina Press is to be commended for its series, First Nations Language Readers, which allows a broad spectrum of readers to enjoy the wisdom, humour, word play and moral lessons inherent in traditional oral stories and legends. Now the press has added These Are Our Legends to the series, and thus preserves seven short Lillooet legends, originally narrated by four Lillooet (Salish) elders from British Columbia’s interior and painstakingly transcribed and translated by Jan van Eijk, a linguistics professor at Regina's First Nations University who has dedicated 40 years to studying the Lillooet language.

The volume offers an interesting juxtaposition. The academically-inclined will appreciate van Eijk’s depth of research, evident in his opening “On the Language of the Lillooet,” in which he discusses phonology, morphology and syntax, and in the extensive Lillooet-English glossary that follows the bilingual stories. His methodology of collecting the stories – or sptakwlh , which translates as “ancient story forever” – via tape recorder between 1972 and 1979 is also included.

These particular stories initially appeared together in a 1981 collection – Cuystw í Malh Ucwalm í cwts (Lillooet Legends and Stories) – and van Eijk imparts the revisions made for the reprint. In explaining how one of the oral storytellers could not provide the precise meaning of two words in a story told to her by her grandmother, the author writes: “Sadly, one almost sees old words fading away before one’s eyes here, a fate that has befallen too many words in too many First Nations languages.” This is why a book like These Are Our Legends is critical.

Linguistics aside, I am guessing that the majority of readers will be most interested in the seemingly simple animal-based legends themselves. “Coyote” is a major force here. This trickster’s antics reveal both the high (intelligence) and low (carelessness) of his (and human) character. In the first story, “The Two Coyotes,” a pair of coyotes are “going along” and one claims he is a coyote, while the other is just “‘another one.’” The former slyly proves his point via a humourous bit of word play. Another example of that original First Nations humour appears in “Grizzly Bear and the Black Bear’s Children,” in which a black-bear-eating grizzly is encouraged to sit on an ant hill and “open [her] bum.”(Interestingly, the glossary includes the Lillooet verb np í gwqam – “to open one’s bum.”)

What I most appreciate here is the “real” — and sometimes surprisingly contemporary — way these stories have been documented in text. A coyote colloquially says “No way,” for example, and in “Coyote Drowns,” the speaker ends thus: “He kept on doing that until he got carried away by the water, and he died, I guess.” Another story includes this: “Gee, when they got there, were they ever amazed ...” Two stories end with the storytellers concluding “That’s all.”

I have the strong sense that I am hearing these stories legitimately, as if the tellers have been drinking tea with me in my kitchen. That, my friends, translates as success.

This book is available at your local bookstore or from www.skbooks.com.